- 3rd Enabling Masterplan Steering Committee, 3rd Enabling Masterplan 2017 – 2021: Caring Nation, Inclusive Society (2016), p. 14.

- National Autistic Society website (accessed 1 March 2020).

- Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) website (accessed 1 March 2020).

- Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) website (accessed 1 March 2020).

- Amelia Teng, “MOE to set up 3 new autism-focused schools; more peer support initiatives for special needs students” The Straits Times (Singapore), 8 Nov 19.

- Ministry of Education (MOE) website (accessed 11 November 2020).

- Ang Hwee Min, “Professional development roadmap for special educational needs training for mainstream educators to be rolled out”, Channel News Asia (Singapore), 4 March 2020.

- Ministry of Education (MOE) website (accessed 1 March 2020).

- National Autistic Society website Siau Ming En, “Support offices on campus for special needs students”, Today (Singapore), 8 March 2014 (accessed 14 September 2017).

- United States Government Accountability Office, “Youth with Autism – Roundtable Views of Services Needed During the Transition into Adulthood”, Report to Congressional Requestors, October 2016.

- Ministry of Education website (accessed 17 Aug 2020).

- Michael D. Kogan, et al., “Prevalence of parent-reported diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder among children in the US, 2007”, Pediatrics 124, no.5 (2009).

- Kristen K. Criado, et al. “Overweight and obese status in children with autism spectrum disorder and disruptive behavior.” Autism 22, no.4 (2018).

- New Jersey Department of Education website (accessed 17 Aug 2020)

Introduction

Given the growing numbers of persons on the autism spectrum and the increasing longevity of Singaporeans, including those with disabilities [1], it is ever more important that quality services and programmes are made available to cater to persons on the spectrum throughout their lifespans.

To ensure optimum standards, best practices must be evident in all autism services and programmes, be it in early intervention, education, workplace training, healthcare, Day Activity Centres (DACs), leisure and recreation programmes, residential living, etc. The presence of skilled support persons, whether they are caregivers or professionals, is key to the effective implementation of these best practices.

Best practices will differ among service and programme offerings due to differences in their purpose and objectives, so it is essential that a set of evidence-based standards is identified for each type of service or programme, with these standards disseminated among the service providers.

In the United Kingdom, one example of such a process is the Autism Accreditation conducted by the National Autistic Society (NAS) [2], which organisations can use to establish themselves as service providers that offer good-quality support to persons on the autism spectrum. Using pre-determined standards, the NAS provides accreditation to a wide variety of organisations, such as colleges, prisons, schools, local authorities, etc.

While many autism services in Singapore may not currently meet the rigorous standards required to obtain accreditation, a set of clear quality standards would be a good reference point for all service providers to improve their programmes for persons on the spectrum.

Current Situation

| Summary of Current Situation | |

|---|---|

| Current Provisions | Gaps |

|

Early Years

|

|

|

School Years [SPED]

|

|

|

School Years [Mainstream]

|

|

|

School Years [IHLs]

|

|

|

Adult Years

|

|

Over the last few years, autism services and programmes in Singapore have expanded:

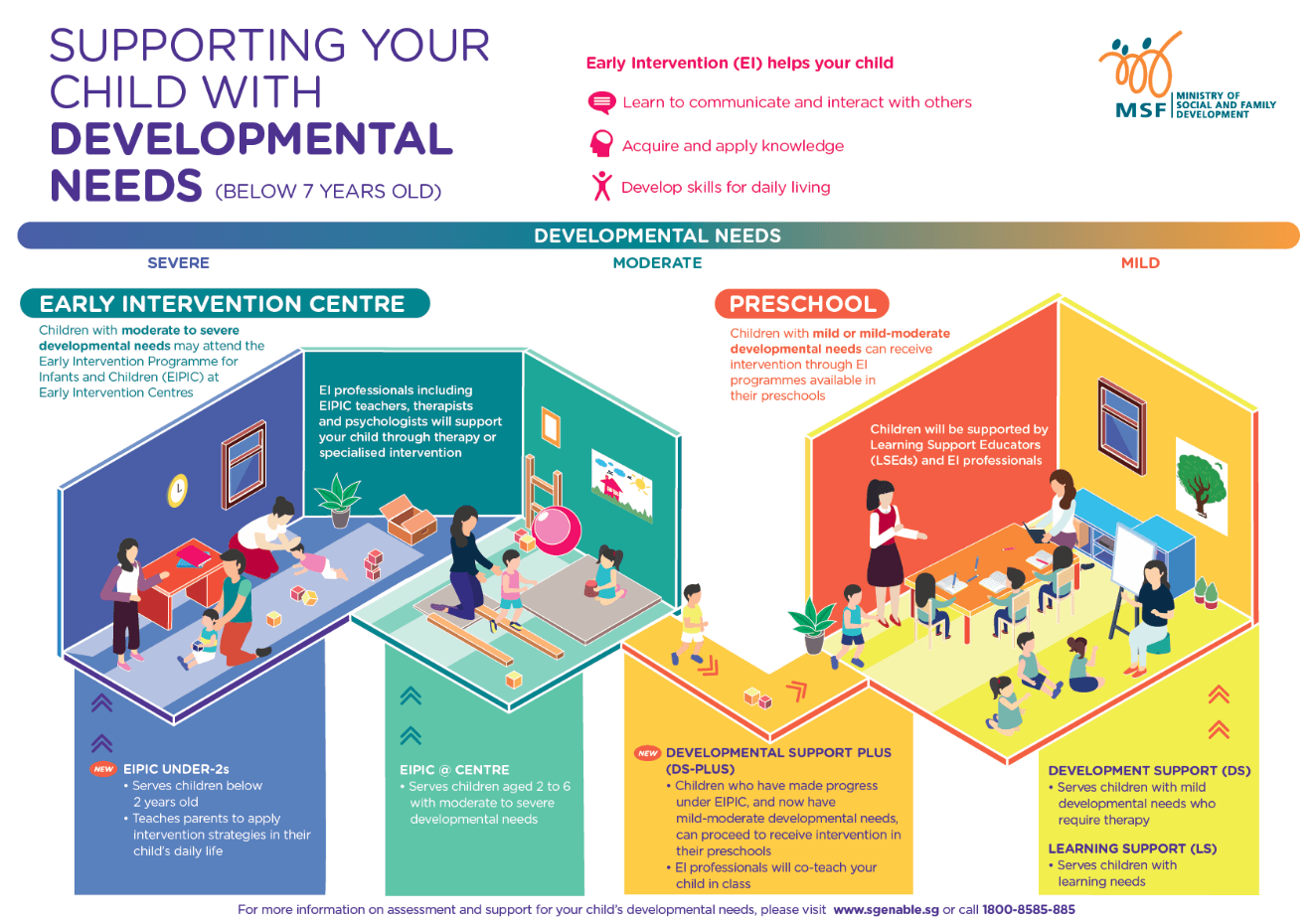

There is now a continuum of early intervention (EI) services under two broad categories – Early Intervention Programme for Infants and Children (EIPIC), and the Development Support (DS) & Learning Support (LS) programmes [3]. See Figure 3 for an infographic depicting the various EI services.

The continuum of EI services includes:

- EIPIC @ Centre: 21 centres at present. 5 to 12 hours per week.

- EIPIC Under-2s: 21 centres at present. 2 to 4 hours per week.

- DS-Plus: Conducted in preschools. 21 centres at present. 2 to 4 hours per week.

- DS & LS: Provided in ~550 preschools [4].

At all these EI providers, the adoption of the Early Intervention Benchmarking Framework (EIBF) is underway. The benchmarking uses a combination of tools, one of which is the Early Childhood Holistic Outcomes (ECHO) framework, which is currently being adapted to the Singapore context. Such benchmarking is an important step towards ensuring high quality early intervention services.

However, as these benchmarking frameworks are necessarily generic so as to be applicable to early intervention services across all types of disabilities, their effectiveness may be limited.

As such, not all EI centres and preschools consistently deliver a curriculum (i.e., content, pedagogy, assessment) that specifically meets the needs of young children on the autism spectrum.

On the training front, the Early Childhood Development Authority (ECDA) is currently developing a set of competencies and training roadmaps for all early childhood and early intervention professionals. However, as 1) this competency framework and training roadmap is not autism-specific, and 2) as long as there are insufficient structured training programmes to equip EI professionals to deliver the full continuum of early intervention services for those on the spectrum, there will continue to be an insufficient number of qualified professionals to deliver such services effectively for young children on the autism spectrum.

Approximately 20% of students with special needs in Singapore attend special education (SPED) schools. [5] SPED schools for students on the autism spectrum (i.e., AWWA School, Eden School, Pathlight School, Rainbow Centres, St. Andrew’s Autism School) typically serve those with moderate-to-severe autism, as they require customised, long-term, and targeted intervention in an alternative educational setting.

In 2012, the Ministry of Education (MOE) introduced the SPED Curriculum Framework (Figure 4) to guide SPED schools in the design and delivery of quality and holistic education to enable their students to attain disability-specific Living, Learning and Working (LLW) outcomes.

MOE and the National Council of Social Service (NCSS) also provide a variety of funds to SPED schools (e.g., Teaching and Learning Fund, Curriculum Enhancement Fund, Tote Board Social Service Fund) to meet the learning needs of students on the spectrum.

Despite these provisions, students on the spectrum at SPED schools may not have their learning needs (e.g., communication, social relationship skills) addressed through their school curriculums and hours.

Like the Early Intervention Benchmarking Framework (EIBF) mentioned above, the SPED Curriculum Framework is designed to be general and flexible, and therefore may not provide adequate direction for SPED schools to design and deliver curriculum content that specifically meets the individual needs of students on the spectrum.

Furthermore, curriculum content for building such skills is largely undeveloped in Singapore. SPED schools must often rely upon their own resources and/or external consultants to develop curriculum content that cater to the learning profiles of their students. As there is no common core for reference, this is sometimes done through adapting local or overseas curricula to suit their needs.

At the same time, SPED school leaders also report that they find it difficult to identify and hire specialised personnel to perform these activities – there is a shortage of qualified autism professionals who have the required “dual expertise”, i.e., being well-versed in curriculum development as well as having experience in autism pedagogy.

In September 2020, MOE introduced a new Human Resource (HR) package for SPED teachers termed “The SPED Teaching Profession: Journeys of Excellence Package”, also known as the Journeys Package. The Journeys Package feature a new SPED Teacher Career Framework, a clear SPED Teacher Role Profile and Competency Framework, as well as a Training Roadmap to equip teachers with the identified competencies. [6]

As some SPED schools and their parent charities have existing HR frameworks covering staff competencies and compensation, there is the need for a review to finalise what would work best on the ground.

On the training front, as part of the MOE-proposed Journeys Package, all SPED teachers will receive training provided through the Diploma in Special Education (DISE) within 12 months from being hired by the individual SPED schools.

As these newly hired teachers will need to teach and support students on the spectrum before they begin DISE training, SPED schools have had to develop their own autism training programmes to prepare the new teachers as soon as they join the service.

Aside from the issue of timeliness and the more generic nature of the DISE, there is a need for further training even after DISE graduation in order for teachers to adequately teach and support students on the spectrum (including those who have co-morbid intellectual disabilities).

To this end, there are several options. It is in MOE’s plans that the National Institute of Education (NIE) will provide a Certificate in Teaching Students with ASD. Alongside this are other professional development courses organised by other training providers, such as ARC(S), Principals Academy, Rainbow Centre Training & Consultancy, SG Enable, Social Service Institute (NCSS), etc.

It is important that SPED schools be always given a menu of choices so that the education needs of students of different autism profiles are covered. Furthermore, in all these courses, it will be important that content covered:

- addresses the specific living, learning, and working needs of different profile groups, and

- is aligned with frameworks and practices at the individual SPED schools to facilitate the transfer and application of learning.

Today, an estimated 80% of students with special needs study in mainstream schools in Singapore. These students go through the mainstream curriculum to prepare them for national examinations (i.e., PSLE, ‘N’ Levels, ‘O’ Levels).

All pre-service teachers are introduced to special needs in a 12-hr segment within a core course on special needs. A small group of staff in mainstream schools also receive additional training to teach and support students with special educational needs (SEN):

- 10% of primary and 20% of secondary school teachers are Teachers Trained in Special Needs (TSNs). This core group of teachers undergo a specialised 130-hour training course to be certified as TSNs.

- At least 1 Allied Educator (Learning and Behavioural Support) [AED(LBS)] is present in every primary school and most secondary schools. AED(LBS) receive foundational training before being deployed to mainstream schools.

The training that these educators receive is relatively comprehensive, and it has been observed that educators generally have good awareness of special educational needs. However, they are typically not skilled enough to manage actual cases that require more support. Although a whole-school approach for SEN support is said to be adopted in the mainstream schools, its actual implementation is less than ideal.

Furthermore, participants in several focus groups highlighted that the number of AED(LBS) in each school may not be sufficient to meet student needs. AEDs also presently receive less training on teaching and supporting students on the autism spectrum as they are no longer expected to specialise in specific developmental conditions. Opportunities to deepen their knowledge about specific conditions are also difficult to come by due to limited vacancies in such professional development courses.

In March 2020, MOE announced the introduction of a professional development roadmap to enhance special educational needs training for all educators (including allied educators) in mainstream schools. Bite-sized online learning resources will be launched in phases to help all educators better support their students with special educational needs (SEN). [7]

Institutes of Higher Learning (IHLs) in Singapore comprise Institutes of Technical Education (ITE), polytechnics and publicly funded universities. About 2,500 SEN students are enrolled in IHLs each year, [8] of which approximately 40% are on the spectrum. [9]

Higher education settings places new demands on all students (e.g., large class sizes, more group work), but compared to other students, youths on the autism spectrum require more support from educators who have received autism-specific training. [10]

In Singapore, about two-thirds of academic staff in IHLs have undergone basic training to support students with special needs [11]. Every IHL also has a SEN Support Office (SSO) which provides a one-stop service in supporting students with SEN from pre-enrolment to graduation. At times, some SEN officers at ITEs and polytechnics provide direct intervention to their students with SEN on non-academic skills, such as social skills, self-regulation, and life skills. However, this can be quite limited –SEN officers are often willing, but they are often not sufficiently equipped or have the bandwidth to help.

To better support students on the spectrum in IHLs, the Autism Support Programme developed by ARC(S) and Temasek Cares in 2013 provides training for students on the spectrum and staff who work with them in Junior Colleges, Polytechnics and ITEs. The programme is ongoing and supports about 80–100 students on the spectrum each year.

Despite these initiatives, consultations and focus group discussions with SEN officers and individuals on the spectrum indicate that the learning supports for students on the autism spectrum are not systematically provided in IHL settings as they can often depend on the goodwill of the faculty/staff to customise the course materials.

In addition, it was reported that there is low interest in staff awareness and training workshops in IHLs for teaching and supporting students with SEN. Some faculty/staff perceive SEN issues as too time-consuming or do not regard them as priority in their work.

Adults on the autism spectrum who have high support needs are generally unable to join the workforce. Quality day care programmes are important for this group because unlike their employed peers, a large part of their day is free and therefore, unstructured, time.

At present, there are 7 autism-specific Day Activity Centres (DACs) in Singapore:

- Eden Centre for Adults @ Clementi (Capacity: 44)

- Eden Centre for Adults @ Hougang (Capacity: 44)

- SPD Day Activity Centre (Capacity: 30 for autism programme)

- St. Andrew's Adult Autism Services –- Day Activity Centre (Siglap) (Capacity: 73)

- St. Andrew's Adult Autism Services – Day Activity Centre (Sengkang) (Capacity: 50)

- THK Autism Centre @ Geylang Bahru (Capacity: 70)

- Blue Cross Thong Kheng ASD Day Activity Centre (Capacity: 50)

The total capacity of DACs in Singapore adds up to 361 places, yet at least 3,000 adults with autism in Singapore would stand to benefit from day care programmes: 15%–20% of individuals with ASD have conditions that can be described as “severe”. [12]

Also, as the different DACs are operated by different social service agencies (SSAs), intervention and training models vary across them. There is no consistent or established standards-of-care or regulatory framework available that caters to the needs of adults on the spectrum.

As for health and wellness, adults on the spectrum also report that clinical services with autism expertise are limited in Singapore. There is insufficient capacity and capability to support both physical and mental wellness among individuals on the spectrum. As such, access to preventative medical services (e.g., mammograms, annual health screenings) for individuals on the spectrum are limited as well.

There is a need for this issue to be addressed, because when compared to the general population, research conducted overseas show that conditions such as obesity, hypertension and diabetes are more common among children and adults on the autism spectrum. [13] Anecdotally, the frequency of these conditions among persons on the spectrum in Singapore appears to be high as well.

Presently, there are no specialised outfits that cater to persons on the spectrum with regard to their physical wellness. As for mental wellness, the Neurobehavioural Clinic (NBC) – Autism Services at the Institute of Mental Health serves children and adolescents between 6-18 years old with autism, and the Adult Neurodevelopmental Service (ANDS) at the Institute of Mental Health treats adults on the spectrum who suffer from co-occurring mental health conditions (e.g., depression, anxiety disorders and psychotic disorders) or problem behaviours.

Recommendations

The following are some recommendations for this high priority area.

With the rapid proliferation of autism services and programmes in Singapore, there is an urgent need to ensure that quality standards are upheld to increase the likelihood of desired outcomes.

Hence, evidence-based quality indicators should be explicitly defined for all services and programmes that target persons on the spectrum, bearing in mind that these indicators will differ across different types of services and programmes.

For example, on the health and wellness front, a refresh of the AMS-MOH Clinical Practice Guidelines on Autism Spectrum Disorders in Pre-School Children (2010) and an expansion of its guidelines to cover a person’s entire lifespan are recommended. This is one of the ways to guide the development of quality standards for health professionals in monitoring both the physical and mental wellness of persons on the autism spectrum. Such standards must also be established for early intervention, education, workplace training, healthcare, Day Activity Centres (DACs), leisure programmes, residential living, etc. Other examples of quality programme indicators for students on the spectrum can be found in Autism Program Quality Indicators (2004), published the by New Jersey Department of Education. [14]

These standards should be tiered – e.g., basic to advanced – such that identified basic indicators should be evident in all autism services and programmes in Singapore, while the advanced indicators should be consistently applied by those service providers aspiring to deliver the highest standards of autism services and programmes for those on the spectrum.

When these quality standards have been established, an accreditation process could be considered for the different services and programmes. This would ensure that quality standards are consistently implemented by service providers.

Furthermore, when quality services and programmes have been readily identified through an accreditation process, it enables caregivers and organisations to make informed decisions about which services and programmes would be the most appropriate for their children, students and clients, thus minimising the loss of time, opportunity and resources.

Quality services and programmes require the efforts of skilled support persons, whether they are caregivers or autism professionals, to achieve effective implementation. As such, capability and capacity building are essential to this process.

To that end, structured and comprehensive autism-specific competency frameworks and training roadmaps should be developed to further the skillsets of caregivers and autism professionals. The training roadmaps should also incorporate a clear coaching and mentoring framework to support learning and practice

These frameworks and roadmaps for caregivers and autism professionals will serve as a guide for training providers in developing suitable learning programmes. These programmes must be closely monitored and audited, ensuring that the content and approaches are consistently up-to-date and evidence-informed, incorporating latest global research findings and inputs from domain experts. This will ensure sound and professional levelling up of the entire sector.

Technology can also be leveraged to quickly equip caregivers and autism professionals by curating web-based training programmes that deliver evidence-based and evidence-informed practices in a bite-sized manner. The curated list should be continually updated to reflect current best practices. Echo Autism, which provides families and professionals real-time access to a virtual learning network consisting of autism experts, may be a useful reference model.

Finally, given the diversity in profiles of those on the spectrum, there should also continue to be a diversity of courses and providers in the training landscape, as well as an appropriate degree of autonomy for each caregiver and SSA/school to select from these options to meet their specific needs.