- 2nd Enabling Masterplan Steering Committee, 2nd Enabling Masterplan 2012 – 2016 (2012), p. 30.

- Government of South Australia Department of Education website (accessed 3 March 2020)

- West, Darrell M. “The need for lifetime learning during an era of economic disruption” Brookings Brown Center Chalkboard (USA) (18 May 2018)

- Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) website (accessed 1 March 2020).

- Amelia Teng, “MOE to set up 3 new autism-focused schools; more peer support initiatives for special needs students” The Straits Times (Singapore), 8 Nov 19.

- Ministry of Education (MOE) website (accessed 13 October 2020).

- Amelia Teng and Priscilla Goy, “Children with moderate to severe special needs to be part of Compulsory Education Act” The Straits Times (Singapore), 8 Nov 16.

- Amelia Teng and Fabian Koh, “MOE accepts panel's recommendations on compulsory education for special needs children” The Straits Times (Singapore), 17 Nov 17.

- Nienke M.Ruij and Thea T.D.Peetsma, “Effects of inclusion on students with and without special educational needs reviewed” Educational Research Review 2, no.2 (2009).

- Ministry of Education (MOE) Factsheet on Facing Your Fears Programme (accessed 18 Feb 2020)

- Dawn R. Hendricks, and Paul Wehman, “Transition From School to Adulthood for Youth With Autism Spectrum Disorders” Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 24, no.2 (2009).

- Roux A. M. Shattuck P. T. Rast J. E. Rava J. A. Anderson K. A. (2015). ‘National Autism Indicators Report: Transition into Young Adulthood’. Philadelphia, PA: A.J. Drexel Autism Institute, Drexel University.

- Paul Wehman et al. “Transition From School to Adulthood for Youth With Autism Spectrum Disorder” Journal of Disability Policy Studies 25, no.1 (2014).

- SG Enable website (accessed 10 March 2020).

- SPD website (accessed 10 March 2020)

- SPD website (accessed 17 Aug 2020).

- NUS High website (accessed 10 March 2020)

- Autism CRC website (accessed 10 March 2020)

- Mr. Eric Chen’s personal website (accessed 29 November 2020)

- Joanna Seow, “National Jobs Council will create jobs and training opportunities on an unprecedented scale: Tharman” The Straits Times (Singapore), 3 Jun 20.

Introduction

Education develops each person’s abilities and strengths, thereby enabling them to realise their full potential.

This is certainly the case for persons with disabilities too – a quality education from a young age will prepare them well for their adult lives as independent and contributing members of society. [1]

For students on the autism spectrum, successful and positive school experiences are dependent on: [2]

- Awareness and knowledge of teachers and school leaders about autism.

- How schools accommodate the learning needs of students on the spectrum.

- Utilising an individual’s strengths and interests across the curriculum.

- Building and sustaining positive relationships between families and schools.

At the same time, it is important to note that education is not limited to just the school-going years. In fact, for many persons on the spectrum, the acquisition of knowledge and skills required for living and working as adults is rarely complete by the time formal schooling ends.

For one, students on the spectrum may not routinely have their core learning needs met (i.e., areas that those on the spectrum typically struggle with, such as self-regulation, flexibility, communication, or social relationship skills) through their school curriculum, because formal schooling especially in mainstream settings may emphasise the mastery of academic content or technical skills. When these learning needs are not met fully, persons on the spectrum can find it difficult to obtain and maintain employment, or to live independently as adults.

Even when the core learning needs of those on the spectrum are targeted in school, teachers and students are likely to require more time to complete the process of teaching and learning, since the skills must be taught explicitly, and repeated real-world practice is often required for students to attain mastery. This is especially so for students on the spectrum who have high support needs or those who also have co-morbid intellectual disabilities.

It is vital that opportunities for lifelong learning are available to everyone. [3]

This is particularly so for persons on the spectrum living in the current age of rapid technological and economic transition – their preference for routines may make it difficult to adjust to changes with how daily living tasks are completed (e.g., the current move towards a cashless society in Singapore). Furthermore, the types of work that people on the spectrum often excel at, particularly those which are repetitive in nature, are increasingly being automated.

Current Situation

| Summary of Current Situation | |

|---|---|

| Current Provisions | Gaps |

|

Early Years

|

|

|

School Years [SPED]

|

|

|

School Years [Mainstream & IHLs]

|

|

|

Adult Years

|

|

There is a continuum of early intervention (EI) services in Singapore at present:

- EIPIC @ Centre: 21 centres at present. 5 – 12 hours per week.

- EIPIC Under-2s: 21 centres at present. 2 – 4 hours per week.

- DS-Plus: Conducted in preschools. 21 centres at present. 2 – 4 hours per week.

- DS & LS: Provided in ~550 preschools.

In 2019, the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) further enhanced subsidies for EI services and broadened the income criteria for means-tested subsidies so that these services would become more affordable and accessible to all families of children with developmental needs. [4]

However, not all EI centres and preschools consistently deliver a curriculum that specifically meets the needs of young children on the autism spectrum (see High Priority Area A – Quality Assurance for Autism Services).

Approximately 20% of students with special educational needs attend SPED schools in Singapore. [5] In the last two decades, the capacity of autism-specific SPED schools has rapidly increased to meet the growing numbers of children on the spectrum in Singapore.

There are currently five SPED schools for students on the autism spectrum. In December 2020, MOE announced further efforts to enhance SPED accessibility for students with moderate-to-severe SEN needs, including those who are on the autism spectrum. It is expected that by 2027, there will be 10 SPED schools for students on the autism spectrum. 4 of these schools will support students on the spectrum who can access the national curriculum. [6]

In 2019, the Compulsory Education Act was extended to include children with moderate to severe special needs (including those on the spectrum), acknowledging the importance of a quality education for each Singaporean child, regardless of their learning challenges. [7] The Compulsory Education Act requires that all Singaporean children complete six years of primary education in national schools before they turn 15 years of age. [8]

MOE has also lent significant support to SPED schools, increasing provisions to allow for smaller class sizes, higher numbers of support staff, additional support funding (e.g., High Needs Grant), and greater customisation in educational approaches. However, there is still room for improvement as evidence-based and evidence-informed best practices (see High Priority Area A – Quality Assurance for Autism Services) may not be consistently practised by all educators in the autism-specific SPED schools.

The remaining 80% SEN students attend mainstream schools in Singapore. Like other students, they go through Singapore’s curriculum in preparation for the national examinations (i.e., PSLE, ‘N’ Levels, ‘O’ Levels). Such an inclusive approach is generally a positive step – research has shown that inclusive education benefits both students with and without disabilities in areas of academic achievement and socio-emotional functioning. [9]

However, reports from educational professionals on the ground, families and the individuals on the spectrum indicate that the education provisions in mainstream schools may not be sufficiently comprehensive to ensure successful and holistic outcomes for students on the spectrum.

Importantly, areas of learning that address core autism challenges are not always targeted in a systematic manner within mainstream settings.

There are several reasons for this, which are elucidated below.

First, as most neurotypical students do not require explicit instructions in specific areas of social functioning or daily living skills (e.g., friendship skills, self-regulation, organisational skills), a student on the spectrum in a mainstream setting would most likely not receive much-needed instruction in these areas where they potentially have skill gaps in. Several individuals on the spectrum in Singapore who spent most of their school years in mainstream settings reported that their interactions with neurotypical students could have been improved with some level of soft skills training, such as friendship skills and the understanding of social dynamics.

Second, students on the spectrum in mainstream schools follow the national curriculum set by MOE. Their eligibility for the next level of education weighs heavily on their academic scores, which is no different from other neurotypical peers. As such, teachers and allied educators say that there is often insufficient time to build non-academic skills for students on the spectrum as schools typically focus on completing the academic curriculum to prepare students for the national examinations. Allied educators also report that they can sometimes be overstretched due to heavy caseloads. Hence, the fragile balance between academic and non-academic student outcomes often ends up with the academic taking precedence.

That being said, it should be noted that in recent years, MOE has rolled out a “Facing Your Fears” (FYF) programme for students on the autism spectrum in several secondary schools (67 schools, as of 2019 [10]). Under the FYF programme, AED(LBS) in schools are trained in an evidence-based intervention programme to support students who have anxiety. This is certainly a step in the right direction, with students on the spectrum receiving training and support that directly addresses some of their core challenges.

Schools in Singapore also play an important role in preparing its student for employment. In all SPED schools, MOE has put in place several employment-related processes and programmes:

- Framework for Vocational Education to guide SPED schools in designing a structured vocational education programme.

- School-to-Work (S2W) Transition Programme, developed in collaboration with MSF and SG Enable, matches graduating SPED students to suitable training or employment pathways based on their strengths, interests and job preferences.

- Roll-out of structured Transition Planning process in all SPED schools, supported by MOE (as mentioned in High Priority Area B – Planning for Life).

At mainstream schools and Institutes of Higher Learning (IHLs), there are general provisions for all students:

- Structured Education and Career Guidance (ECG) curriculum is typically in place as early as Primary 3 in mainstream schools.

- Numerous mainstream secondary schools have work attachment, work experience or job shadowing programmes to enable students to learn directly about working life and working environment.

- Completing an internship is frequently a requirement for IHL courses. Internship programmes provide students with an authentic work experience so that they can be more ready for future employment. For students who are unable to secure external internships, IHLs often support them by offering in-house internships.

Despite these programmes and processes, reports from potential employers and job coaches suggest that students on the spectrum still tend to be under-prepared for working life.

They often have gaps in employability skills, such as work habits, communication skills, interpersonal skills, and have a weak understanding of work culture. These gaps exist because students on the spectrum may need a longer runway to prepare for employment. They will also require continuous training and support.

One possible way to start addressing these gaps is through structured internship programmes. Research with persons on the spectrum examining barriers to employment have demonstrated the importance of work experience, internship programmes and supported employment schemes.[11] For example, researchers found that employment rates in the United States for those aged 21–25 were over twice as high for adults on the spectrum who worked for pay during high school (90%) versus those who did not (40%).[12]

Likewise, positive findings were shown in a US internship programme that arranged work placements within community businesses (e.g., banks, hospitals, or government departments) for young adults on the spectrum – 87.5% of the group who participated in the scheme achieved subsequent employment, compared to 6.25% in the group who did not take part. [13]

These findings demonstrate that internship programmes are vital to prepare students on the spectrum for work and boost their chances for obtaining future employment. However, across SPED schools, mainstream schools and IHLs, the availability of such internships in Singapore for students on the spectrum appears to be a key stumbling block.

However, unless training and coaching support are available to prepare students on the spectrum before and during internships, the chances of success are low.

At SPED schools, the feedback from school leaders is that there are still limited internship opportunities for their students as they face difficulties in engaging industry partners for such programmes. Furthermore, the S2W programme typically does not cater to the profiles of most of their students on the spectrum.

At mainstream schools that offer work attachment, work experience or job shadowing programmes, only some students get to participate. Furthermore, the support required for students on the spectrum to benefit fully from the experience of participating in such work attachments is also limited due to lack of awareness and resources.

At Institutes of Higher Learning (IHL), students on the spectrum often face challenges in securing external internship opportunities to obtain authentic work experiences. Few companies are willing to accept interns who are on the spectrum, and IHL faculty/staff often have concerns about jeopardising their existing partnerships. In addition, there is limited training and support available to students on the spectrum to prepare them for, and during, their internships. Hence, some fail to complete their external internships or are unable to benefit fully from the experience.

In Singapore, SG Enable administers the SkillsFuture Study Award for Persons with Disabilities (worth $5,000), which recognises and supports persons with disabilities in enhancing their employability. [14] Persons on spectrum are also eligible for the APB Foundation Scholarship for Persons with Disabilities (worth $12,000), administered by SPD, for the pursuit of higher education in local universities. [15] There have been several persons on the spectrum who have received this scholarship, with the most recent being Mr Daniel Liew in 2019. Mr Liew is a National University of Singapore (NUS) student studying statistics and business analytics. [16]

However, there are very few structured learning programmes in Singapore to cater for individuals on the spectrum in essential skills for employment and independent living.

Post-SPED school learning options are limited. Most SPED students stop learning, whether in daily living or for work, enduring a ‘cliff effect’ phenomenon after they complete their formal years of school.

Lifelong learning, which is the goal of Singapore’s SkillsFuture movement, is not accessible to many adults on the spectrum. Most SkillsFuture offerings do not provide the needed disability learning support, and trainers are rarely equipped to teach persons on the spectrum and may therefore choose not to enrol prospective trainees who disclose their autism condition. As such, many adults on the spectrum run the risk of their skills becoming obsolete.

Adults on the spectrum also report barriers for accessing higher education in Singapore: accessibility and availability of supports for learning, as well as rigidity in the entry criteria for higher education.

Recommendations

The following are some recommendations for this high priority area.

Whether in SPED or mainstream educational settings, there must be a strong emphasis on preparing persons on the spectrum for independent living and work from an early age.

Due to the nature of autism, persons on the spectrum may not instinctively develop the daily living skills required for living independently as adults, and they may also face challenges in acquiring an intuitive understanding of work culture or the soft skills that are essential to obtain and maintain employment.

To improve the outcomes that adults on the spectrum have in independent living and employment, the following strategies are recommended:

- Introduce residential training programmes to provide for extended time and space for students on the spectrum to acquire daily living skills. These residential programmes should feature fruitful collaborations with families and community partners. The Boarding Programme [17] at NUS High School of Math & Science may be a model worth exploring.

- Teach employability skills to students on the spectrum from a young age in all school settings, with a strong emphasis on imparting soft skills such as work habits, communication skills and interpersonal skills, to address the key difficulties that characterise autism. ARC(S)’s E2C has begun work to develop programmes to teach these employability skills and further collaborations with partners can prepare students from young.

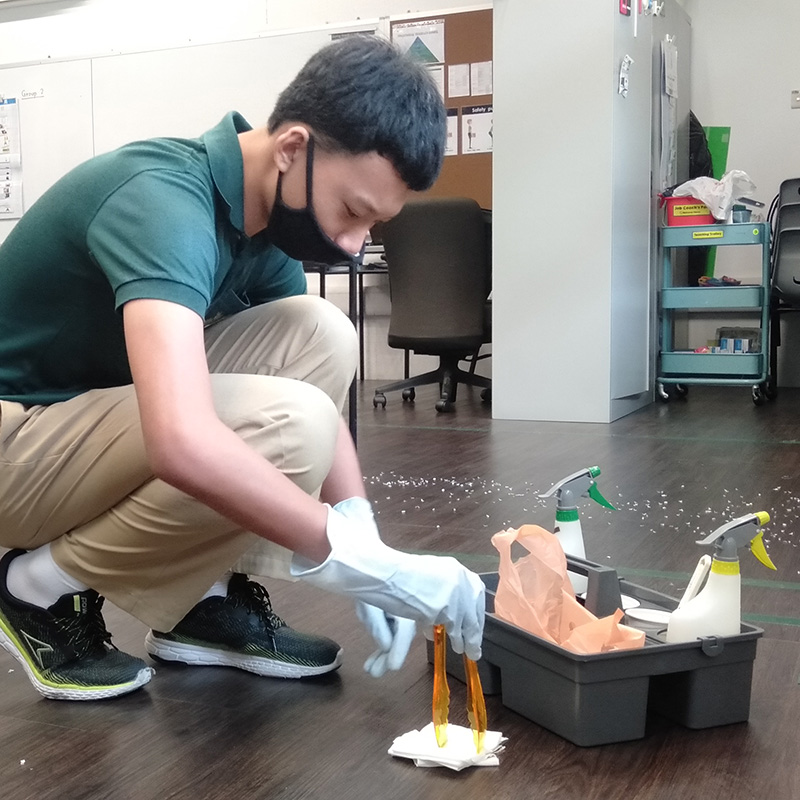

Students at Eden School learning employability skills Photo: AA(S)

- Develop supported 'Train-Place-Train' internship programmes for students on the spectrum in partnership with businesses in the community so as to first teach them the skills needed for the workplace, place them as interns and provide the necessary coaching and training even during internships.

With the inclusion of children with moderate to severe special needs within the framework of the Compulsory Education Act, [07] it would be timely to review the models of education and support for students on the spectrum in all educational settings.

Areas for consideration include how schools can best equip students with the pivotal skills required to improve post-18 quality of life outcomes, and learning support models (e.g., pull-out models where students with special needs work with the Allied Educator/SEN officer in a separate setting outside of the main classroom, vs. push-in models where the Allied Educator/SEN officer supports the student within the main classroom, etc.), among others.

The findings should subsequently be disseminated to guide all schools in implementing the appropriate education models for their students with special education needs.

A menu of services or programmes should also be developed and made accessible in all educational settings. This allows for the appropriate customisation of each student’s education, ensuring that they receive education provisions that uniquely meet their learning profiles and needs. For example, a student who demonstrates difficulties with the English language may, under advice, choose from programmes that target reading, comprehension, or writing, etc. Another student who needs help with his or her social functioning may be offered programmes relating to self-regulation, friendship skills and communication skills, etc.

It is recommended that students, families and schools collaborate to select from this menu of services to support each student in making progress towards his/her broader and long-term needs.

Identify and build a pool of local and overseas trainers and consultants, which should include individuals on the spectrum, as part of an “Autism Learning Academy”. The Academy should look into systematically identifying and analysis the learning needs of those on the spectrum to draw up a comprehensive lifelong learning and development roadmap.

This roadmap should consider:

- building up the strengths and talents of each person on the spectrum,

- bridging the gap skills that are specific to those on the autism spectrum, and

- leadership development, from self-mastery to organisational leadership.

Skills should be clearly identified, with indication of whether and how learning is currently met for each skill (e.g., through school, through external training programmes, etc.) It is hoped that the roadmap will support each person on the spectrum (with the inputs from the person’s family and his/her team of autism professionals) to prioritise his/her learning needs at each stage of life, resulting in improvements in the quality of life.

Developing the leadership capacities of persons on the spectrum will enable them to better advocate themselves and make decisions about their own lives, as well as empower them to bring about positive impacts to their own community. The Future Leaders programme, which is delivered by and for adults on the spectrum and supported by the Autism CRC and Aspect Australia, is a model that is worth considering. [18]

In Singapore, a few adults on the spectrum, such as Mr. Eric Chen and Mr. Wesley Loh, banded together in 2018 to set up a network of WhatsApp chat groups to bring the autism community in Singapore together. The aim is to enable and empower persons on the spectrum by providing leadership opportunities and support to their peers, juniors, and caregivers. Mr Eric Chen has also recently in November 2020 proposed ideas to provide solutions for persons on the spectrum with low support needs in Singapore. [19] These projects speak to the growing desire for individuals on the spectrum for self-determination and self-advocacy. Mr Eric Chen has approached ARC(S) for support of his plan. ARC(S) believes there is an opportunity for collaboration for like-minded adults on the spectrum and key autism service providers such as ARC(S) and other members of ANS.

The “Autism Learning Academy” would also source, develop and deliver learning solutions that cater directly to individuals on the spectrum. Such learning solutions range from those that address core autism challenges, to others that address the QoL domains important to persons on the spectrum.

Given the threats of disruption and automation in this current day and age, many adults on the spectrum feel that they may not be “future-ready”. Many work tasks that those on the spectrum have a natural affinity for tend to be repetitive and detail-oriented in nature, such as data entry work. Unfortunately, these are the very jobs that become redundant due to automation.

To mitigate the fallout of disruption and automation, it is recommended that a Skills Council taskforce, involving representatives from job training and placement agencies, industry leaders, SG Enable and Ministry of Manpower (MOM), is set up to identify skills required for jobs that are suitable for persons on the spectrum (and other persons with disabilities) in current as well as future industries and businesses, such as IT and quality control. This taskforce may tap on the recently announced National Jobs Council that has been established to grow jobs and training opportunities for all Singaporeans in response to the fundamental shifts in our economy caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. [20]

The identified skills by the said Skills Council should likewise be incorporated into the learning and development roadmap for persons on the spectrum (Recommendation C.3) and form part of the workings of the “Autism Learning Academy”. Taking a more robust and proactive approach will ensure that persons on the spectrum who are able to work will continue to be relevant for the workplace.