- Patricia Howlin, Jennifer Alcock, and Catherine Burkin, “An 8 year follow-up of a specialist supported employment service for high-ability adults with autism or Asperger syndrome” Autism 9, no.5 (2005).

- Katherine Gotham, Steven M. Brunwasser, and Catherine Lord, “Depressive and Anxiety Symptom Trajectories From School Age Through Young Adulthood in Samples With Autism Spectrum Disorder and Developmental Delay” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 54, no.5 (2015).

- Michael D. Kogan, et al., “Prevalence of parent-reported diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder among children in the US, 2007”, Pediatrics 124, no.5 (2009).

- KL Curry, M P Posluszny, and S L Kraska, “Training criminal justice personnel to recognize offenders with disabilities”, OSERS News in Print 5, no. 3 (1993).

- T Brugha, et al. Estimating the Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Conditions in Adults: Extending the 2007 Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey, The NHS Health and Social Care Information Centre (2012).

- 3rd Enabling Masterplan Steering Committee, 3rd Enabling Masterplan 2017 – 2021: Caring Nation, Inclusive Society (2016), p. 116.

- Valerie Koh, “Autistic youth’s mother urges greater understanding of people with special needs” Today (Singapore), 9 May 2016.

- Neo Chai Chin, ‘Viral’ video of autistic man masturbating on MRT train sparks calls for greater empathy Today (Singapore), 22 September 2018.

- ICAPS Facebook Page (accessed 29 Nov 2020)

- Operation Housecall website (accessed 17 Aug 2020)

Introduction

“Life After Death” is a term coined by Mr. Eric Chen, one of Singapore’s first autistic self-advocates. It refers to the importance of individuals on the spectrum to be able to continue to thrive even after their caregivers have passed on.

However, many adults on the spectrum do not have the means to secure their future financially.

Multiple studies have indicated that a substantial percentage of adults on the spectrum either face long-term unemployment or are engaged in sheltered or voluntary employment.[1],[2] Furthermore, some 15–20% of individuals on the spectrum have conditions that can be described as “severe”.[3] These adults may not be able to advocate effectively for themselves due to a variety of reasons, e.g. communication, mental health issues, etc.

Furthermore, mainstream services in the community, such as polyclinics, banks, public service offices etc., can be difficult to access for many individuals on the spectrum. This is in part caused by a lack of understanding of autism among staff, but there are other factors at play as well. Some individuals on the spectrum may suffer from sensory issues (e.g., hypersensitivity to light and noise), while others may struggle with the formats or language used in official forms or information guides due to communication difficulties. For adults on the spectrum, these are all barriers to community access.

Furthermore, overseas research has shown that children, youth and adults on the spectrum are seven times more likely to have brushes with law enforcement officers than their typical peers.[4] More recent studies have shown even higher numbers, indicating that individuals on the spectrum tend to be overrepresented in the criminal justice system.[5]

As such, many ageing caregivers are anxious and worried about what will happen to their adult children on the spectrum after they have passed on or become incapacitated themselves.

Their worries range from financial, legal, housing, healthcare and other issues. In recent years, there have been books published (e.g., Life’s Missing Manual for Families with Autistic Children by One Estate Solution; Safeguard Your Family’s Future by Benjamin Foo) and agencies set up to help parents plan for the future. However, many families and caregivers continue to live in worry and fear, with little access to information about how to begin planning for an uncertain future.

Current Situation

| Summary of Current Situation | |

|---|---|

| Current Provisions | Gaps |

|

Increasing Access to Community Services

|

|

|

Supporting Families in Future Planning

|

|

The 3rd Enabling Masterplan states that “frontline staff in various public service agencies, for example, hospitals, police and community centres, should be equipped with the knowledge and trained so that they can communicate with customers with disabilities more effectively”,[6] emphasising the importance of making reasonable adjustments to ensure that community services in Singapore are accessible to persons with disabilities, including persons on the spectrum.

At present, basic awareness training on autism for frontline staff at public agencies is conducted by ARC(S) upon request. Till date, this initiative has been taken up by organisations such as the Singapore Police Force, SBS Transit and Sentosa Development Corporation.

Several dentists have been trained to provide care for patients with special needs. In 2016, the Geriatric Special Care Dentistry Clinic (GSDC) was set up by the National Dental Centre to provide specialised and holistic dental care for the elderly and special needs patients.

In 2015, the Appropriate Adult for Persons with Mental Disability (AAPMD) scheme was established; it aims to assist persons with intellectual disabilities, autism, and/or mental health issues when they are required to give statements to the police during investigations.

However, public members, including those on the frontline, are often unaware of how best to respond to persons on the spectrum. [7],[8]

Support for persons on the spectrum within the criminal justice system is inadequate for the following reasons:

- Volunteer training in the AAPMD scheme is not sufficiently differentiated for persons on the spectrum, thus reducing the effectiveness of the assistance rendered.

- Effectiveness of the Appropriate Adult activation is compromised by incorrect assessment of the situation, especially in complex cases.

- Lack of case management for persons on the spectrum in the prison system.

Regarding the process of future planning, there are a few different schemes, services and programmes in Singapore to support families:

- The Special Needs Trust Company (SNTC) is a non-profit company supported by the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) that provides trust services to provide a steady income stream for persons with disabilities after their caregivers pass on.

- The Special Needs Savings Scheme (SNSS) enables parents to set aside CPF savings for the long-term care of their children. The child will receive monthly pay-outs of an amount pre-determined by the parents until the savings are exhausted.

- Assisted Deputyship Application Programme (ADAP) launched by MSF in which parents or caregivers may, where appropriate, obtain Mental Capacity Assessment reports by psychologists of the SPED schools that their children attend to support their applications to become their children’s deputies when they turn 21 years of age.

- NTUC SpecialCare (Autism) Insurance provides coverage for the person on the spectrum if he/she should suffer from a permanent disability, protection from personal liability, or requires hospitalisation.

However, as end-of-life planning is a complex and sensitive matter, with many issues coming into play, families sometimes find it very difficult to put together a plan that will ensure that their adult child on the spectrum will be sufficiently cared for after their passing.

Furthermore, the ADAP programme is only limited to current SPED school students and selected DACs and sheltered workshops. There are many adults on the spectrum in the community whose families need support to obtain the requisite Mental Capacity Assessment reports. Such a report from the Institute of Mental Health (IMH) can cost over $1,300, after which the family will still have to navigate the complex legal system to apply for deputyship.

In addition, while there are merits to having SPED school psychologists perform the mental capacity assessments as part of ADAP, some SPED schools report that they are not sufficiently resourced to do so, especially for cases where the adolescent or young adult on the spectrum has an uneven cognitive profile and/or scattered knowledge and skills.

Comprehensive insurance coverage still remains inaccessible for most persons on the spectrum.

Adults on the spectrum and caregivers report that when procuring insurance coverage, they often face discrimination by insurance agencies, such as having their applications rejected or having to accept additional loading fees and over-reaching exclusions.

In 2020, Mr Wesley Loh, an autistic self-advocate, started a movement, Insurance Coverage for Autistic Persons – Singapore (ICAPS), to advocate for essential insurance policies (e.g., hospitalisation, critical illnesses, life insurance) to be accessible to all persons on the spectrum through government laws and national policies.[9] Several forum letters have been written to the Straits Times, and they were received positively by both the autism community and the relevant government agencies. The advocacy group continues to explore solutions to ensure better insurance coverage for persons on the spectrum in Singapore.

Recommendations

The following are some recommendations for this high priority area.

To support parents and caregivers in the process of planning for the life of the person on the spectrum after they pass on, an organised and straightforward step-by-step guide is crucial.

This process should involve the person on the spectrum as well and should be considered as an extension of the person-centred life planning as mentioned in Recommendation B.2.

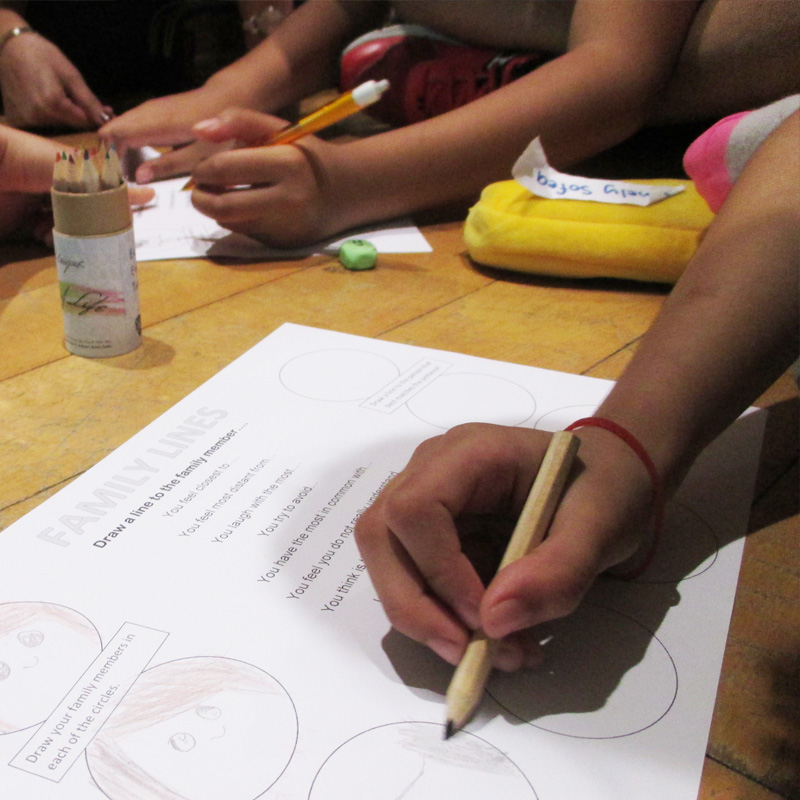

Although there are books already published on this topic, caregivers still struggle to access the necessary information, suggesting that the current format may not meet the needs of these families. Other ways of presenting and disseminating the information that may be considered are workbooks or templates that families can work on together in a systematic way. “Thinking Ahead: A Planning Guide for Families” published by the Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities (UK) may be a useful reference. Facilitated workshops and/or consultation services to complement this process may also increase the number of families who can prepare for their children’s future at an early stage.

A “Life After Death” workgroup of caregivers and other volunteers has been set up since October 2020, with the support of ARC(S) and AA(S), to begin gathering currently available literature and resources in preparation of the said “playbook”.

For many families, the tasks of teaching, supporting, and raising a child on the spectrum is shared by everyone in the family – the parents, the siblings, and sometimes, the extended relatives as well. Siblings often play the role of substitute caregivers while growing up, and many may feel that they have no choice but to take on this role officially after their parents pass on. These roles can sometimes be physically and emotionally challenging, and siblings can sometimes feel overwhelmed by their responsibilities.

A sibling support group can connect and support siblings on the spectrum via their shared experiences and peer group support, helping them to realise that they are not alone in their predicament, and giving them their own space to share their experiences.

At present, AWWA School and St. Andrew’s Autism School each provide sibling support programmes, specifically in the form of annual sibling camps. The camps aim to address the socio-emotional needs of these siblings, including having better understanding of their sibling with special needs, and their schooling environment; gaining mutual peer support; and exploring and discussing their own personal identities and emotions. These camps target school-aged sibling participants (i.e., between 7 and 17 years old).

Both St. Andrew’s Autism School and ARC(S) also have small platforms for adult siblings to connect with one another. At these groups, participants are invited to share their struggles as well as their achievements, providing a space for the siblings to learn from and support one another. Such support groups are particularly important for adult siblings who may feel the increased pressure of taking on caregiving responsibilities as parents age.

Having a dedicated Sibling Support Network would expand its reach and also deepen the support that the siblings receive. The services of such a Sibling Support Networks can be further extended in the future to include respite programmes (e.g., taking turns to care for one another’s siblings to allow time to run errands or have a self-care break).

First, expand the reach of ADAP to more adults with special needs and increase the resources available to the programme. In situations where more complex cases render ADAP unsuitable, expand the reach of affordable mental capacity assessment by mental health professionals in hospitals and private practice. At the same time, expand the reach of legal services to persons and families affected by autism by training and improving access to justice. The first step would be to ensure that criminal justice agencies (e.g., police, courts, prisons) have access to specific expertise that support persons on the spectrum.

Second, structure yearly training for all frontline staff in public service agencies, potentially by leveraging caregivers and individuals on the spectrum as educators (see Operation House Call by The Arc[10]) and develop evidence-based guidelines for managing autism within the administration of criminal justice settings.

Third, establish community “safe places” with trained staff (e.g. cafes, libraries, gyms) where people with special needs can seek help when they meet with challenging situations when out and about in their community. These safe places should be marked clearly so that they are readily identifiable by those who may require their assistance.

Fourth, set up “neighbourhood support groups” with grassroots volunteers and local social service agencies, to support persons on the spectrum and their families in the local vicinities.